Ivan T. Sanderson — Chapter 7 — Radio and TV Appearances

First radio show on the BBC in 1930. First television on same in 1938.

Beginning in 1948 both radio and television series were initiated in New York on NBC in the field of the natural sciences, the latter with live wild animals. These were as follows:

1948–49 15-minute, 5-day a week over radio WNBC, New York.

1949 One 1-hour a week Radio roundtable on science, NBC, two 1/2-hour per week TV programs over WNBT.

1950 5, 15-minute Radio per week over WBAL, Baltimore, one 15-minute TV over WEAL-TV, Baltimore. (Science & Research Director, Station WBAL.)

First Commercial Color-Television program in history for CBS ("The World is Yours"), 5-days a

week, 1/2 hour, for 6 months.

Once a week, 1/2 hour-long, color-telecast for CBS. ("New Horizons")

1951–52 five 15-minute weekly Radio over WSTC, Stamford, Connecticut, on behalf of the Stamford Museum and Zoo.

1951–58 Once a week regular Feature spot on the Garry Moore morning show, with live animals.

1960–1973 Numerous guest and spot appearances on both radio and TV on all networks and many local stations. (Average four per month)

ITS: When I finally settled down here [in the U.S.], I had been, of course, in radio and television. I had bought imported live animals to show on early television. I had the first [color] television program after the war here.

Earlier it was mentioned that Ivan's mother was an investor who helped finance the work of John Logie Baird. He was the first person produce a live, moving, grayscale television image from reflected light, in 1926, based on a mechanical scanner (Nipkow disk). He also patented a system which later became known as radar. He assisted the BBC in starting the first public television service that began on August 22, 1932. From 1932 to 1935, the BBC produced programs in their own studio at 16 Portland Place. Baird also established the world's first major TV Studio and Broadscasting Complex at the Crystal Palace in South London. In 1935 the BBC moved their BBC Television Service to a leased section of the Alexandra Palace, North London's counterpart to the Crystal Palace. Public broadcasts of "high-definition" television were made from this site starting in November 1936. Two broadcast studios were set up to test two competing systems, the Marconi-EMI's 405-line electronic scanning system and Baird's 240-line mechanical scanning system. The systems transmitted on alternate weeks until the 405-line system was chosen in 1937.

One broadcast in 1938 would include the young naturalist Ivan Sanderson appearing with a live elephant. How they transported an elephant through Alexandra Park onto the first floor of the Alexandra Palace is probably an interesting story in itself. Ivan did about six other TV shows before the start of World War II in Europe. It was not until he came to America, however, that he really became involved with regular programming on both radio and TV.

RG: I think your first TV show was called The World is Yours.

ITS: No, the first thing I did in this country was a 15-minute radio show five days a week over station WNBT, which was the local outlet for NBC in New York. That was in 1948.

During 1949 I had two half-hour TV programs per week over WNBT. Every Tuesday I did a show on natural history and every Friday I did one on the natural history of industry, because all industry is founded on mining, or water, or the air, or plants or something. It dealt with the background of it. I also had a weekly hour-long radio show that same year over the NBC network. I did it with scientists on the “technicalities” of science—a roundtable discussion.

RG: But you also had a show called The World is Yours.

ITS: Well, that was the first color television program. That was on CBS. It was the first one ever regularly broadcast in color, the first one ever.

Then I had a show; Bulova Watch were my sponsors and I took over from Arthur Godfrey. It was an hour—every day, five days a week, with hot lights in the middle of the summer, for one hour. Whew! And the girl they gave me to work with turned out to be a biology teacher and her name was Patty Painter. She weighed about 90 pounds. At the end of every show for a year she fainted, that poor thing, because the heat became so terrific.

RG: Five days a week?

ITS: Five days a week, one hour. Sir, I tell you, it was something. It was done in a big studio up at 98th Street in New York [Note: Actually, Ivan is referring to the CBS Color Studio 57 in the Peace Theater at 1280 Fifth Avenue, on the Northeast corner of 109th Street, nicknamed, "Father Divine's Studio."] And they had all hot lights in those days—the strip lights. No air conditioning. You couldn’t have the fans on because it upset the audio. It was right at the corner of Central Park, and it was a real hot New York summer. Whew! I’ll tell you, and we were hauling elephants in and giraffes out. And this poor little girl, she was game as anything, but every day she just fainted. She was a real old showgirl, you know? A real trouper. She stuck it out and as the lights turned off, Patty 'rooop—bang!' and somebody would catch her. Oh, that was a nutty one.

Ivan's Co-Host, "Miss Color Television"

It's not surprising that Patty Painter would faint, since even black-and-white television in those days required far more intense lighting than today’s color systems. Moreover, the CBS color television system used for Ivan's shows in 1951 demanded four times the studio illumination of then-existing black-and-white television systems.

It's not surprising that Patty Painter would faint, since even black-and-white television in those days required far more intense lighting than today’s color systems. Moreover, the CBS color television system used for Ivan's shows in 1951 demanded four times the studio illumination of then-existing black-and-white television systems.

Patty Painter's real name was Patricia Marguerite Stinnette (August 30, 1929 – August 10, 2003). She was a petite (5-foot, 1.5-inch, 95-pound), vivacious, highly talkative, auburn blonde with dark hazel eyes, a perfect cream complexion and ruby lips. Born in Morgantown, West Virginia, to Mr. and Mrs. Gaynes Pierre Stinnette, Patty moved when she was five to Beckley, West Virginia, where her parents became the managers of the Beckley Credit Bureau and ran it for many years.

Patty Stinnette was a descendant of Britain's William de Shackelford of the 1500s, himself a descendant of Henry de Shackelford, a Gentleman-in-Waiting for Henry V circa 1390, who was himself the descendant of Baron Jacques-le-Forte, a Norman nobleman and an officer in the army of William the Conqueror during the latter's conquest of England in 1066. William the Conqueror granted him the land that became the ancestral seat of the Shackelford family in Godalming Parish, Surry County, England, about 40 miles southwest of London.

Patty graduated from Beckley's Woodrow Wilson High School at the close of World War II. (The school's present-day librarian, Debra Walker, was able to find her in the "Echo" yearbook as a senior in 1945. She was voted "Why Teachers Go Mad" and "Wittiest" that year in the senior superlatives. Her senior picture quote read, "Full of mischief, but still necessary to the senior class.")

Patty left Beckley, traveling to New York in 1946 with both her mother (the former Gertrude E. Smith) and grandmother (Mrs. Sarah Etta Smith, the former Sarah Etta Shackleford), taking up residence in a Manhattan apartment (in 1951 they all moved to Elmhurst, Queens, on Long Island). Accompanying them was their double-yellow-head parrot, who cried out,"Trouble! Trouble!" whenever the TV set was switched on—something of an omen, as we shall see. Patty soon sound found employment with the John Robert Powers modeling agency and quickly became a successful magazine and advertisement fashion model. (There is no evidence that she was ever a biology teacher, as Ivan mistakenly claimed.)

Painter/Stinnette was nicknamed "Miss Color Television" around CBS long before her frequent appearances on early color TV broadcasts, because she was actually involved in helping CBS develop its own pioneering form of color television, the CBS Field Sequential Color System. It was all an accident. As a Powers fashion model in 1946, CBS called the company, asking for some models with television experience. Powers sent over some tall, elegant fashion models, who sat with blank expressions in front of the color cameras, and whose pale blue eyes didn't photograph well. CBS called back, asking Powers to send over somebody else, quick. They sent Patty, who was a "commercial" model, "the wholesome kind who turn up in beer ads or who model mostly hands and feet," as Patty would later recount in 1951.

Patty rushed over to the CBS studios, then still situated at 15 Vanderbuilt Avenue above Grand Central Station, wearing what should have been a too-casual $13 Jay-Thorpe rayon jersey beach dress with blue, green, pink, and yellow vertical stripes, size nine. (She later said that she had heard the job involved color television and so she wore her most colorful outfit.) Upon reaching the CBS studio, Patty was positioned on an old, tall backless wooden stool. Feeling perfectly relaxed, she uttered a few words—she never suffered from stage fright, nor was she ever at a loss for words. The director soon emerged from the control room and said, "Well, honey, I guess you're it. Start tomorrow morning." Later accounts placed technicians and CBS Color inventor Peter Goldmark in the control room too, who allegedly told the director in person that he wanted Patty for the job, thanks in part to her "beautiful, perfect skin... a delicate complexion," as director Frances Buss later described her in an Archive of American Television interview.

When Patty asked what she should wear, the director replied, "What you're wearing is all right, dear." Patty ended up wearing that dress for four years. "It became an obsession with me," she later said. Wearing it eight hours a day for four years gave it the appearance and consistency of a flour sack. Patty would take her talisman to a dry cleaner on 44th Street in Manhattan, but she felt it was too "risky" to have the dress actually dry cleaned. Instead, the staff was instructed to forego the use of any equipment or harsh chemicals, and to gently rub out the spots and brush out any dirt by hand. During this period, the style of dresses changed, with hemlines dropping three inches. A stagehand chided her, suggesting that she "drop her hem" and "get back in style". The superstition of the talisman dress ultimately spread to the rest of CBS. Patty would recall how during some "important demonstrations" her superiors, "would have me wear it as a slip under something else, for luck." (This would most likely be for members of the FCC or perhaps "God Himself," as CBS head William S. Paley was known to his staff.) One such important demonstration occurred in January 1947, when CBS transmitted a color television picture from the Chrysler Building 40 miles to a receiver set up in the Tappan Zee Inn in Nyack, New York, a luxury hotel on a hill overlooking the widest section of the Hudson River. From a room there, FCC Chairman Charles Denny spoke to Stinnette by phone and watched the teenager play with different brightly colored scarves on a CBS color television receiver equipped with a 12-inch screen.

After four years of wearing it, she retired the dress and its supernatural powers to a closet in her apartment.

Patty could sing and dance, but never did so in all of her years in front of the test cameras:

"Most of the time I just sit in a folding leather chair in the color laboratories while they photograph me," she said, when asked how she managed to sit out four years of experiments.

"Sometimes I knit, and sometimes I talk about the brightly-colored props that they put in front of me. I just say whatever comes into my head." [Toomey, Elizabeth. "Color TV's Leading Star since 1946 Has High Hope of Having Audience Soon." United Press International (30 October 1950). Long Beach (Calif.) Press-Telegram. Friday, October 31, 1950. p. A9.]

Scarves were another running joke of sorts. When testing began in 1946, the experimenters became fascinated with how their color reproduced on a TV monitor. "In the beginning, I just held up scarves," she would say. "I held up so many scarves we began to call CBS color 'the scarf sequential system'."

A CBS vice president visited the set one day, carrying an apple from his brother's farm. Patty took a bite on camera, everybody thought it was a great visual and audio test for the equipment, and so she would sometimes chomp on up to eight apples a day. Fortunately, she was fond of apples. She usually ended each day on camera eating an apple, and she almost always finished each apple down to the core.

Additionally, the CBS technical staff were always changing her hair color for the cameras, sometimes three times a week, which once caused a large hunk of it to fall out when her hairdresser Betty was combing it at Guillaume Roberts.

"The most people who ever saw one of my shows was 600 who attended a special demonstration one time in Washington," Patty recalled. "I was so pleased that I nearly got the giggles." [Toomey, Elizabeth. "Color TV's Leading Star since 1946 Has High Hope of Having Audience Soon." United Press International (30 October 1950). Long Beach (Calif.) Press-Telegram. Friday, October 31, 1950. p. A9.]

Perhaps no other performer in the history of television has made so many appearances before the cameras and been seen by so few people. [Philip Hamburger. The Talk of the Town. “Miss Color.” The New Yorker. August 11, 1951, p. 20.]

Myra Sue Roush, of Woodlawn Avenue [Beckley, West Virginia], corresponds regularly with 22-year-old Miss Stinnette and reports that "aside from the glamorous life that she lives, Patty still keeps up with her church work." ["Ex-Beckleyan Appears as New York 'Cover Girl'." Beckley Post-Herald. (West Virginia) Thursday morning. 25 January 1951. p. 3.]

Things became even more bizarre when, in 1948, the pharmaceutical house of Smith, Kline & French approached CBS and Peter Goldmark with a proposal to use color television as a teaching tool for surgery. Black-and-white television was not sufficiently realistic and even confusing to those observing the operations. To Goldmark, color telecasts of operations was a terrific idea and so on May 31, 1949, the first live operation in front of color television cameras took place at the University of Pennsylvania. In December 1949, the Goldmark team demonstrated this system to the American Medical Association's annual meeting in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

Then, somebody thought of Patty...

Now Patty's employers are going to televise operations in color for the benefit of student surgeons and Patty has been picked to undergo the operations.

According to the former Beckley student her bosses meet her every morning and ask her how she is feeling—hoping of course that she will need an appendectomy or some other operation. So far though Patty has been a disappointment to them in that regard since she always answers that she never felt better. ["Beckley Model Makes Good in Television." Beckley Post-Herald. (Beckley, West Virginia) Monday morning. 10 October 1949.]

This story was perfect for some amusing tongue-in-cheek coverage:

Dr. Goldmark would prefer that all the operations be performed on Miss Painter. After all, she knows the television technique. Her blood, furthermore, probably is a brighter shade of red than anybody else's.

"Every morning he asks me how I feel," she said. "He wonders how I'd like to underego a small operation. Of course, he'd rather have a big operation, like removing a foot, but he'd settle for an appendix. And I always tell him that I never felt better. He always seems so disappointed, it's frightening."

That's one way to earn a living. I only hope the pay is commensurate with the risks. [Othman, Frederick C. "Problems of Patty; Video Knife Haunts Rainbow Girl." United Feature Syndicate. The Berkshire Evening Eagle. Saturday 8 October 1948. p. 3.]

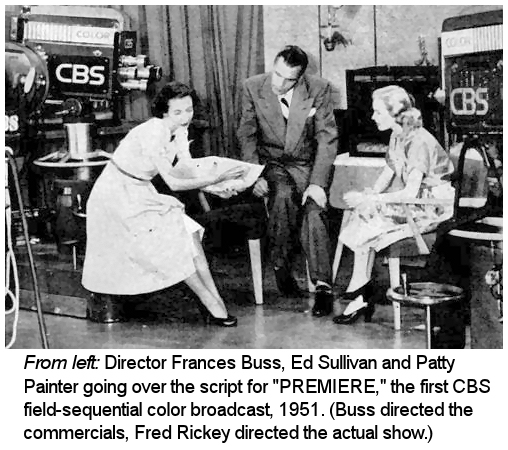

Finally, after serving as a sort of live test pattern for five years, Patty hosted PREMIERE—the very first Commercial CBS Color System telecast on June 25, 1951, from 4:35 p.m. – 5:34 p.m., accompanied by a star-studded cast. She show was produced by Fred Rickey, who also directed. Frances Buss, the associate producer, also directed the commercials for the show. Unfortunately, although five CBS stations were broadcasting the show (New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington, D.C.), there were only about 25 or 30 operating CBS color TV sets in existence on that day.

Her ambitions: "To have a regular color television show of my own and to get married. But I would want to continue in television—my children probably will grow up in Studio B." [Oliver, Wayne. "Patty is the Not-So-Secret Weapon of CBS' Color TV." The Cedar Rapids Gazette. Sunday. 13 May 1951. p. 26.]

One of her wishes was granted on the day following PREMIERE, when she found herself playing straight lady to Ivan Sanderson and his collection of animals on the world's first regularly scheduled color show, a children's Nature program entitled The World is Yours.

Ivan Sanderson's co-host on The World is Yours, "Patty Painter" had the real name of Patricia Stinnette. She was a successful New York City model. Here we see her wearing a jumper worn in a fashion show of school clothes at Bloomingdales. Date unknown, though probably late 1940s. Photo courtesy of her cousin, Patricia Viellenave.

Ivan Sanderson's co-host on The World is Yours, "Patty Painter" had the real name of Patricia Stinnette. She was a successful New York City model. Here we see her wearing a jumper worn in a fashion show of school clothes at Bloomingdales. Date unknown, though probably late 1940s. Photo courtesy of her cousin, Patricia Viellenave. Undated photo of Patty Painter taken at Stallards Studio in her home town of Beckley, West Virginia. Photo courtesy of her cousin, Patricia Viellenave.

Undated photo of Patty Painter taken at Stallards Studio in her home town of Beckley, West Virginia. Photo courtesy of her cousin, Patricia Viellenave. Undated "glamour pose" of Patty Painter. Photo courtesy of her cousin, Patricia Viellenave.

Undated "glamour pose" of Patty Painter. Photo courtesy of her cousin, Patricia Viellenave.

The World is Yours and New Horizons

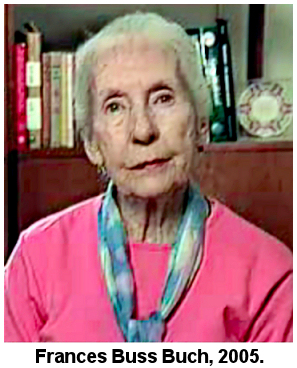

ITS: Then we had a show, the next one was called The World is Yours. This is the one you mentioned before. This was one hour long on Saturday mornings, for young people. [NOTE: Actually, "The World is Yours" was a 30-minute children's nature show broadcast Monday through Friday at 4:30 p.m. It premiered Tuesday, June 26, 1951—making it the first regularly scheduled color show in history (the second was "Modern Homemakers” with Edaline Stohr that premiered a day later, on Wednesday, June 27, 1951). The show was sponsored by General Mills and was directed by Frances Martha Buss (June 3, 1917 – January 19, 2010), the first and apparently sole female TV director of that era . The final broadcast of "The World is Yours" was on September 14, 1951. The Saturday morning show Ivan is referring to here was called “New Horizons.” It was a 30-minute (not hour-long) natural history program Ivan hosted starting October 6, 1951. It was also shown October 13, 1951, and it ended October 20, 1951. It too was directed by Frances Buss.] Beautiful show. I took a different country, a “natural” country every week. We had the music and dancing, and folklore of the country, then the animals, the plants, and the minerals. We did Brazil, for instance. We had diamonds and gold, and we had kinkajous and Brazilian flowers, and then a girl playing the piano, and then we had a whole Brazilian orchestra playing “Brazil.” Then we had some African dances, Brazilian-African dances for the fiestas. Beautiful show, and in color. And CBS color, you see, is what they call the “optical system” not the “compatible” which you have now.The optical system was direct. The colors were better than in Nature. It's like putting on a pair of rose-tinted glasses—beautiful, absolutely. We did a show on orchids once. Well, the Orchid Growers Association were telephoning up and saying: 'But our orchids are not that pretty!' It was better.

RG: Was this on tape?

ITS: Oh no, it was all live in those days.

Then the FCC—there was a kind of political wrangle, and RCA had CBS’s license 'canned' to introduce their so-called compatible system, which is electronic. I had been doing a lot of experimental shows for them with the same Patty Painter for NBC [He is referring to someone else—Patty never appeared on NBC], and also with Ben Grauer—you may have heard his name, he’s a political commentator—he’s still on the air, regular. When CBS lost their license, I moved over to NBC and started the first color show for them. But frankly, color television today, you see, is no good at all. It just isn’t accurate. I mean, suddenly it all goes red, or all goes blue, whereas the optical system was absolutely precise. But, politics is politics, and what can you do?

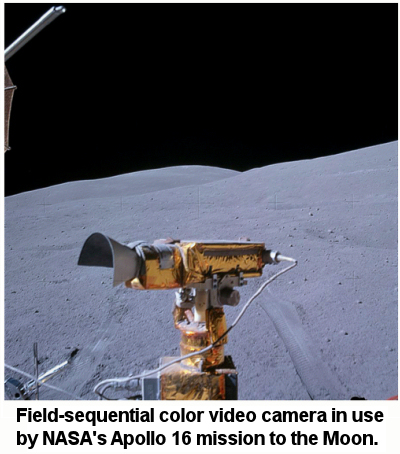

The CBS color system (more correctly called the CBS field-sequential color system), developed by Peter C. Goldmark (1906-1977), was actually a black-and-white TV set-up utilizing two color filter disks, one spinning in front of the camera at the studio and the other spinning in front of the cathode-ray picture tube at home. When these two disks became synchronized, red, blue, and green images would flash on the screen in such rapid succession that to the eye there would appear to be a naturally-hued image on the screen. (To be precise, in a September 1951 Popular Science article, Ted Lawrence, the color-quality supervisor for CBS, was quoted as follows: "The camera is basically a standard model. We've made some electronic changes and added a color disk and a small electric motor to turn it. The camera disk has 12 filter segments, instead of the six segments used in the receivers, so that we can use a slower motor.")

Because the filters used in the studio were of the exact composition as the filters incorporated into the disks of the home receivers, the colors reproduced were absolutely perfect every time—no fine tuning needed. Thus, a CBS field-sequential color system had no 'tint,' 'hue' or 'color' control, since the color filter material in both the camera and receiver were fixed according to the CBS specifications (Wratten filters #26 for red, #47 for blue and #58 for green). At the time of my interview with Ivan Sanderson (1970), all National Television System Committee (NTSC) color cameras used dichroic mirrors reflecting red, green and blue images, respectively, into three orthicon pickup tubes, and color TV receivers employed a cathode-ray tube having red, blue, and green phosphor dots on its surface. Thus, the full color image was "taken apart" in a different way than it was "put back together" in the TV set, which could cause problems. Indeed, a good phoshor for producing the color red didn't appear until 1967, though it apparently didn't go into widespread use. Most phosphors for TV picture tubes were chosen for the brightness rather than their color accuracy. Moreover, the colors of the TV images varied from brand-to-brand, and occasionally from set-to-set of the same manufacturer. Many "color" TV studios used a single monitor in the control room because no two monitors would display an image with similar colors, which made the art of color correction confusing. Moreover, viewers who lived during the era of NTSC color television may be shocked to learn that only one such TV model in history could accurately reproduce the complete gamut of colors of the 1953 NTSC specifications: RCA's very first production model, the CT-100.

Strangely enough, Goldmark's field-sequential color system used for Ivan's CBS color television broadcasts was influenced by the work of TV pioneer John Logie Baird, which, coincidentally, had been funded in part by Ivan Sanderson's mother, Stella.

Baird demonstrated the world's first color TV transmission in Glasgow, Scotland, on July 3, 1928, using Nipkow scanning discs at the transmitting and receiving ends with three spirals of apertures, each spiral having a filter of a primary color (red, green, blue), and three alternating, colored gas-filled light sources at the receiving end (neon for red, helium for blue, and mercury for green), the illumination of each being controlled by a commutator. Baird demonstrated a color system with 120 scanning lines in December 1937, then embraced electronic television, demonstrating a color TV system with 600 scanning lines in December 1940. In 1941, Baird had managed to come up with a mechanical system to transmit color stereoscopic TV images using revolving shutters and disks with red, green and blue filter sectors. His all-electronic "Telechrome" system was first demonstrated to the press on August 16, 1944. He achieved a very high definition color TV image of 1800 lines after World War II.

Baird's rapid sequential-frame color system later influenced the future President of CBS Labs, Peter Goldmark, a man who, as a student in Vienna, had tinkered with Baird's do-it-yourself 30-line television kit of 1926. Goldmark, after seeing and being impressed by the MGM Technicolor movie The Wizard of Oz, began working on the first color TV broadcasting system for CBS in 1940, using a field-sequential system roughly similar to Baird's. Goldmark cobbled together a primitive version of the field sequential system at the CBS Laboratory and showed it to CBS executives in June 1940 on a 3-inch screen placed behind a magnifiying lens. CBS officially began doing non-broadcast "film pickup" color experiments, then apparently did a broadcast over W2XAB on August 28, 1940. Goldmark demonstrated the CBS field-sequential color TV system to both the technical press and a delegation from the FCC on September 4, 1940 (a travelogue broadcast over W2XAB from New York's Chrysler Building) . Tests using live cameras (as opposed to film scanned and transmitted through a coaxial cable) didn't occur until December 2, 1940. CBS began daily color field tests on June 1, 1941 over WCBW. (To see an amazingly detailed chronology of the CBS Color Television System, go to this site by Ed Reitan.)

Baird's rapid sequential-frame color system later influenced the future President of CBS Labs, Peter Goldmark, a man who, as a student in Vienna, had tinkered with Baird's do-it-yourself 30-line television kit of 1926. Goldmark, after seeing and being impressed by the MGM Technicolor movie The Wizard of Oz, began working on the first color TV broadcasting system for CBS in 1940, using a field-sequential system roughly similar to Baird's. Goldmark cobbled together a primitive version of the field sequential system at the CBS Laboratory and showed it to CBS executives in June 1940 on a 3-inch screen placed behind a magnifiying lens. CBS officially began doing non-broadcast "film pickup" color experiments, then apparently did a broadcast over W2XAB on August 28, 1940. Goldmark demonstrated the CBS field-sequential color TV system to both the technical press and a delegation from the FCC on September 4, 1940 (a travelogue broadcast over W2XAB from New York's Chrysler Building) . Tests using live cameras (as opposed to film scanned and transmitted through a coaxial cable) didn't occur until December 2, 1940. CBS began daily color field tests on June 1, 1941 over WCBW. (To see an amazingly detailed chronology of the CBS Color Television System, go to this site by Ed Reitan.)

CBS field-sequential color was first shown to the general public on January 12, 1950. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) adopted it on October 11, 1950 as the official standard for color television in the United States, but it was used in broadcasting solely by CBS for a very short time. RCA had its own system of color television, but it had yet to be perfected for commercial deployment. On October 17. 1950, RCA brought suit against the FCC in the Federal District Court in Chicago to halt the start of CBS colorcasts. A Supreme Court decision in favor of CBS only galvanized RCA and other enemies of CBS to greater action. Various other legal delaying tactics and political maneuvering by RCA ultimately paid off. Although CBS began regularly scheduled broadcasts on June 25, 1951, CBS colorcasts ended on October 20, 1951 when the Defense Production Administration asked CBS to suspend mass production of color receivers in an effort “to conserve materials” for the ongoing Korean War—an act viewed by many historians as a way CBS, which had only about 100 of its color receivers in operation, could gracefully exit the color television war with RCA.

On December 17, 1953, the FCC did an about-face and adopted the more expensive RCA-developed National Television System Committee (NTSC) color system as the U.S. standard. Writing in the February 2003 issue of Ideas on Liberty, Michael Heberling notes that, "It took 23 years (from 1954–1977) until 75 percent of the homes in America had at least one color television." Admittedly, the RCA color system was backward-compatible with black-and-white television sets, unlike the CBS system. Two CBS color sets, a monitor and a slave ("companion") receiver are known to still exist, along with, I believe, a working camera.

Act II: Patty Painter's "Colorless" Life

“There are no second acts in American lives,” said F. Scott Fitzgerald. That could be said of many talented women prior to the 1960s who somehow managed to establish a career and become famous as a result, only to eventually marry, leave their jobs and become housewives, vanishing from the world scene. Pioneering TV Director Frances Buss married and departed CBS in 1954. My own mother left her job in 1956 just prior to the birth of Yours Truly. And then there's the tale of "Patty Painter" (Patricia Stinnette), the "Miss Color Television" of CBS, Ivan Sanderson's co-host on The World Is Yours. When CBS finally abandoned its field-sequential color television broadcasts, the following wry note ("Patti to Lead Colorless Life") appeared on page 5 of the October 27, 1951 issue of The Billboard: "Minor repercussion of Washington's band on color telecasting is that Columbia Broadcasting Company's 'girl rainbow,' Patti [sic] Painter is out of a job. Fem has been CBS's top tint tester for several years now, chiefly in a demonstration capacity. Tradesters wonder if gal will land a berth in CBS black and white. One thing's sure, tho, no matter which web takes custody, the telegeneic blonde is bound to lead a colorless existence from now on."

Patty had signed a five-year contract with CBS back in March 1950 to appear on future CBS Color television shows, but by the end of October 1951 CBS Color programs were no longer broadcast. According to Patty's cousin, Patricia Viellenave (who is named after Patty), Patty planned to star in her own TV series following The World is Yours, but the project fell through and she soon left the TV business. However, she did end up marrying the proposed show's writer, Anthony Dominic Guggenheimer, on February 14, 1953 in St. James Church in Elmhurst, Long Island, New York. Anthony was the son of Harry Guggenheimer and the former Gwendolyn Wormser. (In a 2009 conversation with Ivan Sanderson's animal assistant and right-hand man, Edgar O. Schoenenberger, he said, "I can recall doing Patty a favor. She needed me to drive her to Rego Park, New York, to go see Mrs. Guggenheimer, who I now realize was the woman who eventually became her mother-in-law." Patty, her mother and grandmother lived in Elmhurst, which is coincidentally bounded by Rego Park to the southeast.)

In 1957, the editor of Patty's hometown newspaper wrote the following poignant passage:

Though the Toy Fund had only a mediocre day yesterday, leaving it running a little more than a day behind last year's pace of contributions, we did receive some very encouraging messages from old regulars in the Toy Fund effort.

A total of $24 arrived in letters and from the fine folks who stopped us on the streets yesterday to hand us a dollar here and $5 there.

One of the letters was from a young woman who has been a loyal supporter of the Toy Fund since she was a little girl, something like 25 years ago. Mrs. Patricia Stinnette Guggenheimer of 72 S. Bedford Rd., Chappaqua, N.Y., wrote, "Here is the annual 'Patty Stinnette dollar' with all good wishes for the biggest Toy Fund ever. Good luck and Merry Christmas."

No doubt hundreds of folks will remember "Patty Stinnette" whose family was long in charge of the Beckley Credit Bureau. Patty went on to become a famous artists and photographers model in New York and was MIss CBS Color Television for a long while. Now she is married and has her home and all those responsibilities. But she has never failed to send in her gift for the Toy Fund.

We would bet that Patty, who was sometimes our playmate when we were a wee lad, has contributed to the Toy Fund every year for at least 25 years. And the fact that she now makes her home in New York State has never made any difference. [Hodel, Emile J. "Top O' the Morning; Distant Supporters Boost Lagging Fund." Beckley Post-Herald. (West Virginia) Thursday morning. 28 November 1957. p. 4.]

The Guggenheimers apparently moved to the vicinity of Livingston, New Jersey, in the 1960s, where one of their daughters, Alexis, was born in 1968. The family later moved to southern California.

The Guggenheimers apparently moved to the vicinity of Livingston, New Jersey, in the 1960s, where one of their daughters, Alexis, was born in 1968. The family later moved to southern California.

Patricia Stinnette Guggenheimer died on August 10, 2003 in La Mesa, San Diego County, leaving her husband, two daughters (Alexis Katherine Ward and Melanie Magana), and six grandchildren. She is buried in Holy Cross Cemetery, San Diego, California.

Patty's husband, Anthony, born November 24, 1925, moved to Lovettsville, Virginia about two years after her death where he was a volunteer Investigator of the Loudoun County Sheriff’s Department. He died June 25, 2009 at his residence in Lovettsville, surrounded by his family. [Patricia Viellenave. Personal Communication. 29 September 2009.]

The Path Not Taken

In case the reader is wondering why I've devoted so much space to examining the life of a commercial model who was Ivan Sanderson's co-host on The World is Yours, consider that, upon her death in 2003, no newspaper or other media carried her obituary. Had the CBS field sequential color system won the day over the RCA compatible system, "Patty Painter," armed with her five-year CBS contract, might today be a household name instead of the "poster child" for a case of failed innovation, an odd footnote in the history of television. Like Ivan T. Sanderson himself, Patty has been forgotten by all except her family, a few historians and TV history buffs, and Yours Truly, who has apparently become sentimental in his middle age when it comes to plugging up holes in the historical record.

As it happens, Patty's years of work posing with various objects and gabbing away in front of the experimental cameras helped to supply valuable test data that was later utilized in the 1950s when the CBS system continued to run "underground" so to speak, for the Kline & French (now GlaxoSmithKline) closed-circuit medical color-TV units that Patty used to make fun of back in 1949.

From 1949 until 1958, hundreds of clinical and surgical procedures from some 25 medical schools were transmitted live via cables and microwaved across Philadelphia to large-screen CBS Color TV projectors configured at local medical conventions. These closed-circuit color telecasts often attracted convention audiences of 500 to 700 attendees. It was during such a closed-circuit CBS Color telecast that Dr. Michael DeBakey performed perhaps the world's first televised endarterectomy.

And in a final supreme irony, one of the latter-day specialized applications that employed the field sequential color concept involved the Apollo lunar landing cameras which transmitted color TV images from the Moon during NASA's missions from 1969 to 1972. The head of RCA and NBC, General David Sarnoff, who in the 1940s and early 50s vehemently derided field sequential color television as being too primitive for commercial use, lived to see it become part of America's most sophisticated technological efforts in lunar exploration.

Frances Buss Buch's Recollections

Yours Truly had the great luck of tracking down Frances Buss (later Frances Buss Buch) the former CBS Director of both The World is Yours and New Horizons, who lived in Henderson, North Carolina. (I managed to locate and correspond with her just prior to her death on January 19, 2010.) In a letter dated September 15, 2009, the 92-year old Mrs. Buch offered the following recollections of her days directing history's first color broadcasts with Ivan Sanderson and Patty Painter...

Yours Truly had the great luck of tracking down Frances Buss (later Frances Buss Buch) the former CBS Director of both The World is Yours and New Horizons, who lived in Henderson, North Carolina. (I managed to locate and correspond with her just prior to her death on January 19, 2010.) In a letter dated September 15, 2009, the 92-year old Mrs. Buch offered the following recollections of her days directing history's first color broadcasts with Ivan Sanderson and Patty Painter...

...I am very interested in your info on Patty Painter. When I met her she was Peter Goldmark's TV girl and was used to demonstrate the beauty of CBS Color... Incidentally, I did not direct "PREMIER" on 6-25-51. Fred Rickey did. I directed the commercials which were interposed during the program, from a theatre studio in the Broadway area. I have a Lucite cube, given to me by CBS, thanking me for my contribution to "PREMIERE."

But back to your interest: Ivan Sanderson. I was a staff director at CBS who reported for work at 15 Vanderbuilt Avenue and was handed a work schedule for the day, which might or might not include Ivan Sanderson. I don't recall much about him as an individual. He appeared on time for his scheduled programs complete with wildlife or, I suppose mostly domesticated animals (the largest rat I ever saw was a capybara). He was always in control of his props and production; I merely took the pictures.

I am most interested in your version of how RCA used its influence in Washington to terminate the chances of CBS color being successful. We at the CBS-TV studio, always believed that is how it happened. Of course, incompatibility was the deciding factor, I guess, but then CBS-TV was never in the business of selling TV receivers. The Defense Prod. Administration was heavily influenced by RCA—booo!

Sorry I can't help any further about Ivan Sanderson.... [Frances Buss Buch. Personal Communication. September 15, 2009.]

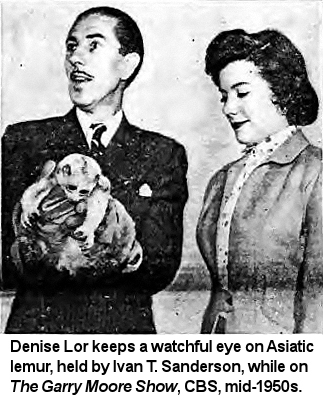

Following the CBS color broadcasts, Ivan Sanderson transplanted his animal showmanship to The Garry Moore Show, from 1951 to 1958. He appeared once a week with rare or interesting animals from the collections he had imported and maintained at his zoo and home in New Jersey.

Ivan also made many appearances on other celebrities' radio shows, such as those of Arlene Francis and Mary Margaret McBride, who was a sort of cross between today's Barbara Walters and Martha Stewart. As talk show host Barry Farber later told me, he made sure that one of the first guests of his career was Ivan Sanderson, because he had read in one of McBride's books her declaration that the most fascinating radio guest to appear on her show in 20 years of broadcasting was Ivan Sanderson. It was McBride who introduced Ivan to Eleanor Roosevelt—who, according to Ivan's close associate, Edgar O. "Eddie" Schoenenberger, "became completely entraced with the charismatic, debonair Ivan, and met him several times." Roosevelt even invited him onto her radio show—she had a radio series produced by the Pan-American Coffee Bureau (28 September 1941 through 4 April 1942) wherein she commented on affairs of the week and interviewed guests, and a 1950-1951 radio series, which followed the same format for 233 numbered programs and an additional 93 interviews. In these series, Mrs. Roosevelt was the hostess and interviewer. Program #223 of this latter series, "the Eleanor Roosevelt Program" was broadcast on 17 August 1951. A tape recording exists: tape 72-30(223), stored at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidental Library and Museum in Hyde Park, New York. On this particular program, her son Elliot, a regular fixture on the show, described Ivan as an author, naturalist, artist and explorer in the realm of natural science. Eleanor then introduced Ivan and the two of them proceeded to discuss his new book at the time, How to Know the North American Mammals. This was followed by Ivan recounting some of his adventures.

Animal Temperaments

Mike Douglas (real name: Michael Dowd), the late talk show host, always complained that animals brought onto his show would answer the call of Nature—on his nice, shiny studio floor. Ivan never seemed to have this kind of trouble, nor did he ever suffer any personal trauma while bringing his animals onto television, even though he was doing so regularly:

I spent ten years hauling wild animals onto television two or three times a week, and I never got bitten, scratched, or even trodden on. This was not just good luck. There was some kind of communication there. I have no idea what it was. Maybe I smelled right to them, or had the right pitch of voice, or I just didn’t care! [Book of Great Jungles, p. 233.]

Some of the plants turned out to be more exciting performers on the air than were the animals:

I myself once had a pitcher plant from the jungles of Southeast Asia which caught a live cockroach on a television show on which I and it were appearing. Unseen by me, the plant snared the cockroach all by its little self, and an alert cameraman who spotted it put the exhibition on the air for the edification of millions. [Book of Great Jungles, p. 160.]

As one of the first "animal experts" to appear on television, Sanderson's abilities to deal with animals of all sorts was known to his colleagues. Jack Hannah Director, Emeritus of the Columbus, Ohio Zoo and Aquarium and host of such nationally sundicated TV series as Jack Hanna's Animal Adventures and Jack Hanna's Into the Wild, paid Ivan perhaps the highest complement when, on a "blooper reel" of outakes, an animal roughed him up a bit and he exclaimed to the TV crew: "I tell you, I'm no Ivan Sanderson!"

But however famously Ivan Sanderson may have gotten along with animals on live TV, the experiences of his hosts and guests could be far less enjoyable.

Africanized Bees?

During the short time Ivan Sanderson was doing those early CBS color broadcasts, his displays of colorful flora and fauna would sometimes get a bit out of control... Here is a reminiscence by a CBS retiree, found on http://www.cbsretirees.com/may1a.htm:

From Cal Marotta

I noticed that my name is not on any crew list so it must be prior to August of 1951. That's when Sather hired me and my first assignment was on Kashouris`s crew. The color studio at that time was on 109th St. and 5th. Ave., I was there until color was cancelled. When I reported to the black & white studios, everybody thought it was my first day on the job. We did two shows a day in color. One was The Ivan Sanderson Show [Note: Marotta is referring to "The World is Yours"]. He was an explorer and every day he would come in with a different animal. One day he had some African bees and they got away. We all ran out of the studio and watched them fly down 5th Ave.

What's so interesting about this is that an urban myth has existed for some years among beekeepers concerning "aggressive New York city bees" and bees there capable of a higher production of honey than elsewhere. As David Graves of Berkshire Berries told Drawger's interviewer Zina Saunders:

"For Berkshire bees, quitting time is about 5 pm. New York City bees, they work harder and longer. And as you can see, we’re here before 7 am, and these bees are already starting to work, whereas the country bees won't be opening the doors till about 9 am. And these city bees will still be hard at work at 7 tonight! Maybe it's because it's warmer here or maybe it's the city lights. Whatever it is, they definitely work longer hours."

When Ivan Sanderson's African bees flew down Fifth Avenue from the CBS 109th Street studio in the summer of 1951, they would have encountered Central Park at 98th Street. The coming winter season would have killed African bees, but had they somehow managed to successfully mate with any local bees before the temperatures dropped, the offspring would have survived and we would be faced with the prospect of Ivan Sanderson having inadvertently bred the first Africanized bees in the Americas! Sounds like a bit of a "stretch," but stranger things have happened, especially when it comes to events in the life of Ivan T. Sanderson, as we shall see.

Jack Lemmon, Arboreal Actor

[More from Cal Marotta:] The other show was called The Mike & Buff Show. Mike was Mike Wallace and Buff was Buff Cobb his then wife. Her father was a very famous jurist. [Note: Cobb, who, according to Frances Buss, pretty much ran the show, was the grandaughter of humorist and columnist Irvin S. Cobb.] One day while Mike Wallace was interviewing a new actor named Jack Lemmon, one of Ivan Sanderson's monkeys got away and climbed up into the grid. Jack Lemmon climbed up a stairwell to the grid and while balancing himself on the pipes (there was no walkway) tried to catch the monkey. It wasn't until his agent screamed at him to get down that he realized what a foolish thing he had done.....ahhhh memories!!!

Assertive Animals

Al Morton, who used to write the "TV Roundup" column which appeared in the Chester Times (of Pennsylvania), enjoyed recounting Ivan Sanderson's animal antics. When Garry Moore (January 31, 1915 – November 28, 1993) launched the fourth year of his hour-long CBS-TV daytime Garry Moore Show in 1953 (Monday through Friday, 1:30 p.m.-2:30 p.m.), Al Morton wrote,

And even though Sanderson often leaves the stage scratched, bitten and bruised, both he and Garry manage to elicit highly entertaining performances from their four-footed friends...

"One thing I've found out about animals," the crew-cut comedian adds, "is that they're almost unpredictable. Like the time Ivan brought a stork to the show. He was explaining that the bird needed a long runway before it could take off. So what does the stork do? Flap its wings and soar out over the audience! It sailed around near the balcony ceiling and then headed straight back for the pit and for Shirley Reeser, my assistant, who sits there during the show timing me. Shirley let out a yell and made a dive under one of the seats."

At another show, a big alligator was the animal guest. It looked sleepy and had to be dragged out on the stage by three men. But the minute it laid eyes on glamorous Denise Lor, the show's vocalist, there was no holding back.

It kept edging closer and closer to her, pulling the three men along with it. When Denise realized that the animal had designs on her—maybe a bite out of her shapely leg—she made a mad dash for the safety of her dressing room. [Al Morton. "TV Roundup. Garry Moore Manages to Keep Cast Intact." Chester (PA) Times. Thursday, October 22, 1953.]

Denise Lor (b. May 3, 1929) was Garry Moore's pretty, vivacious and unsually brave vocalist and comedienne who seemed a living lightning rod for attracting the mischief of Ivan Sanderson's animal friends.

Denise Lor (b. May 3, 1929) was Garry Moore's pretty, vivacious and unsually brave vocalist and comedienne who seemed a living lightning rod for attracting the mischief of Ivan Sanderson's animal friends.

Perhaps her worst moments have been provided by Moore's perennial guest, naturalist Ivan Sanderson. On one show, Sanderson attempted to disprove the superstition that bats infest women's hair. Plucky Denise was picked as the guinea pig, and handled a plaintive ballad with a live bat perched in her coiffeur.

For another show, Sanderson brought a swarm of bees with him, and turned them loose. They flew to the ceiling, were stunned by the hot lights, and landed on stage. By the time Denise was center-stage to deliver "Tenderly," the bees were awake and buzzing around her.

"Oh it was real laughs," she explained, "Like facing a firing squad." [Steven H. Scheuer. "Denise Lor; One Singer Who Must Be Courageous." The Hartford Courant. October 6, 1957. p. 11.]

Lor had a #8 hit recording in 1954 called If I Give My Heart To You (Doris Day did a hit recording of this song the same year). She would go on to appear in many musicals including Gypsy, Annie and Sweeney Todd.

Moore himself had no reservations welcoming Ivan Sanderson and his animals onto his show once a week.

"Next to babies," Moore opines, "everyone loves animals. Even if it's not one of the three favorites (dogs, cats and monkeys)—it may be a goat, a pig, a leopard, or even a skunk. All he's got to do is put his mug in front of a TV camera, and the television audience loves it."

...the whole cast has more fun than a barrel of monkeys and Mr. Sanderson sometimes supplies the monkeys who are funnier than a barrel of people. What more can you ask? [Al Morton. "TV Roundup. Garry Moore Manages to Keep Cast Intact." Chester (PA) Times. Thursday, October 22, 1953.]

And so each week Sanderson had to present some interesting denizen of the animal world on Moore's CBS show: "...bats, anacondas, storks, boa constrictors, porcupines, zebras, crocodiles, baby elephants, skunks, monkeys, chimps, and a young lioness named Blondie. Llucky the Llama became a regular on the show (and even 'married' Llinda Llama onstage), as did a capybara, whose Moore-ish hairdo guaranteed him repeat visits as the star's lookalike." [Marsha Francis Cassidy. What Women Watched: Daytime Television in the 1950s. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. 2005. p. 79.]

And so each week Sanderson had to present some interesting denizen of the animal world on Moore's CBS show: "...bats, anacondas, storks, boa constrictors, porcupines, zebras, crocodiles, baby elephants, skunks, monkeys, chimps, and a young lioness named Blondie. Llucky the Llama became a regular on the show (and even 'married' Llinda Llama onstage), as did a capybara, whose Moore-ish hairdo guaranteed him repeat visits as the star's lookalike." [Marsha Francis Cassidy. What Women Watched: Daytime Television in the 1950s. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. 2005. p. 79.]

Moore's unquestioning enthusiasm for Ivan Sanderson and his animals may have been tested one day, according to a story told to Yours Truly by a Sanderson acquaintance and neighbor, Allen V. Noe, in the mid 1970s. An animal brought out into the bright lights of a television studio often behaves in strange ways. In one such case, Ivan was removing a large boa constrictor from a burlap bag on the Garry Moore Show, when suddenly it wiggled free and headed for Gary, who was now petrified. The snake began to crawl up his pants leg. Gary then jumped a ways up into the air and let out a high-pitched scream, much to the amusement of the audience and crew.

Another moderately hair-raising incident occurred on the morning of Friday, February 22, 1957 (as reported by the United Press), when Ivan brought a sea lion onto the third segment of Moore's show. Everything initially was going well, the creature chomping contentedly on a fish. But then "it apparently took fright at a mike noise."

It scooted to the edge of the stage and plopped into the right side of the orchestra while a capacity holiday crowd of some 650 persons howled. Moore advised the audience to move back. About 100 people left their seats and ran up the aisles. Cameras followed the creature as it waddled under the seats, soon squirming its way to the orchestra's fifth row. Stage hands armed with broomsticks, Garry Moore and Ivan Sanderson "worked frantically for six minutes before they succeeded in boxing it in."

"Said Moore to his panting audience: 'Aren't you glad you came?'"

"The show went on to an uneventful conclusion."

In June 1958 Garry Moore ended his daytime show and moved to a faster-paced nighttime variety show from that ran on CBS from 1958 through 1964, Tuesdays 10 to 11 p.m., and Ivan apparently didn't fit in. Moore was also host of the long-running game shows I've Got a Secret and To Tell the Truth. His final attempt at a variety show, The Garry Moore Show, was produced by Sylvester "Pat" Weaver (Sigourney's father) in 1966, and was scheduled Sunday night following The Ed Sullivan Show. However, it ran opposite Sunday's #1 show in its time slot, Bonanza, was cancelled in mid-season, and so Moore left prime-time for good in January 1967, to be replaced by The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour.

As the Crow Flies...

Ivan Sanderson then tried moving his animal act over to the King of daytime shows, initially with disastrous results. On August 1, 1958 Dave Garroway, host of NBC's Today show (another Pat Weaver creation), had Ivan Sanderson on as a guest. Ivan brought along some birds. First in line was a large, calm, photogenic crow, which practically posed for the cameras and viewers at home. Next, however, came a hawk. The crow took one look at the predator and panicked, flying off into the upper reaches of Studio 3K and landing on an overhead light.

"Please, boy. Come down, boy," Ivan pleaded.

"Here fella, nice fella," Dave cajoled.

The crow stayed put.

Today had just replaced its grueling five-hour format (with two-hour slices for each time-zone) with a new two-hour format tape-delayed for the different time zones (Ampex video recorders were just coming into use). The show had to run like clockwork, and Dave Garroway found himself with a bird perched overhead and a show that had ground to a halt. Panicking, he picked up a studio phone and asked for help. The NBC phone operator, herself panicked that a call for assistance was coming right from host of the Today show live from the studio, apparently misunderstood Garroway's message and placed a dire call for help to the nearest police station.

Within minutes a squad car pulled up to Manhattan's 30 Rockefeller Plaza and several officers dashed into the RCA Building. Storming into Studio 3K they swarmed around Garroway and Sanderson, at the ready to tackle hecklers, gunmen, outlaws, political extremists or what-not.

Instead, they were greeted by the loud cawing (or "scolding" as Ivan would say) of the winged guest perched above them. As Dave Garroway explained that he was in no danger—he simply needed somebody to remove the crow—the show's cameramen were confused as to where they should point their lenses, and the director was cutting between the bird and the confusion below. And then...

The patient officers did an about face and marched out, probably wondering why more television people did not move to Hollywood.

When the show ended Brother Crow was still up on the lights. And, he was still heckling the non-flyers below while they continued their feeble efforts to get him down.

At last report they were magnificently unsuccessful. [Sokolsky, Robert L. "Looking and Listening." Syracuse Herald-American. Sunday, 3 August 1958. p. 26.]

Monkeying Around

Monkeying Around

Ivan Sanderson's next appearance on the Today show, on Wednesday August 13, 1958, was more successful. Ivan decided to celebrate the centennial of the announcement of the Theory of Evolution by bringing on some monkeys. (The confused reader may think that the centennial should have been 1959, because Charles Darwin published his book, the Origin of Species in 1859. But he was still writing up his theory in 1858 when Ivan's historical hero, Alfred Russel Wallace, sent Darwin an essay describing the same idea.) [Vernon, Terry. "Looking and Listening." Press-Telegram. Long Beach, California. Tuesday, 12 August 1958. p. C10.]

Occasional Sightings

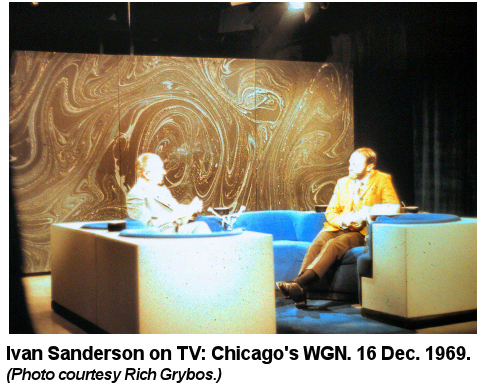

There was a hiatus in Ivan Sanderson's radio and TV appearances from 1958 until 1960, as he took time out to wander through North America in his big station wagon in order to gather material for his coffee table book, The Continent We Live On. Afterwards he went back to do some series on radio, sprinkled with visits to radio and TV shows such as The Long John Nebel Show, The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, the Alan Burke Show, A.M. New York and The Dick Cavett Show, averaging one appearance per week through 1973. For example, at right Ivan is seen doing a talk show on Chicago's WGN on 16 December 1969. (The photo is overexposed; Ivan is seated on the left.)

Home — Next: Chapter 8: UFOs, Caves, Zoos, Fires and Floods — Top of Page